Planting Southern Pines: A Guide to Species Selection and Planting Techniques

Mississippi landowners have made a strong commitment to planting trees over the last several decades. Financial incentives to encourage tree planting spurred additional interest. While some landowners are hesitant to reforest in light of current market conditions, many see the continued benefit and economic viability of planting trees. As these landowners become involved with tree planting, they learn that proper species selection, careful handling, and care of seedlings are vitally important in the success of reforestation investments. Use this publication as a guide for selecting the proper species and handling seedlings throughout all phases of tree planting.

Selecting a Proper Species

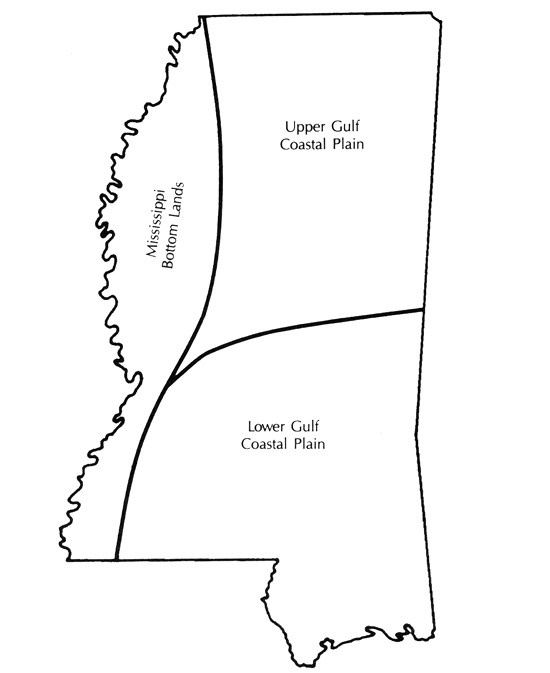

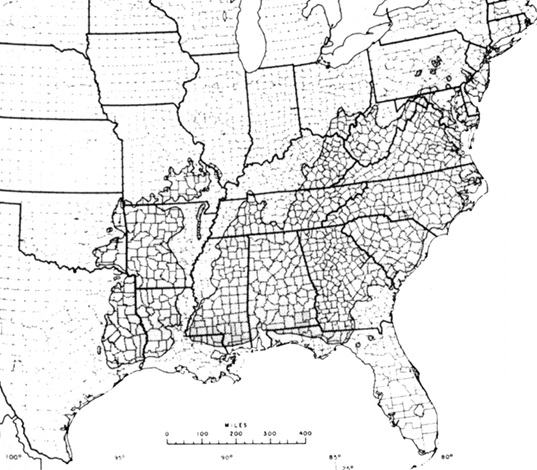

Species selection is the critical first step in tree planting. Maximum growth and yield are possible only if the right species for the particular planting site and geographic location are selected (Table 1). Planting the wrong species on a site results in poor survival, poor growth, and low product yield. Geographic location limits species choice (Figure 1). For example, slash and longleaf pine planted in northern Mississippi suffer from branch and stem breakage when ice forms on needles.

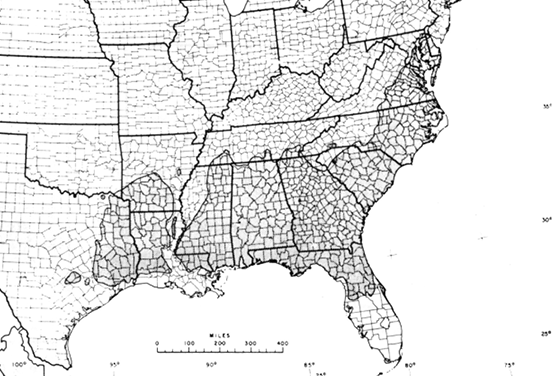

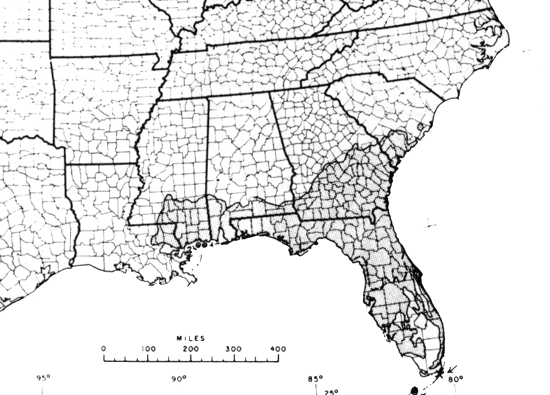

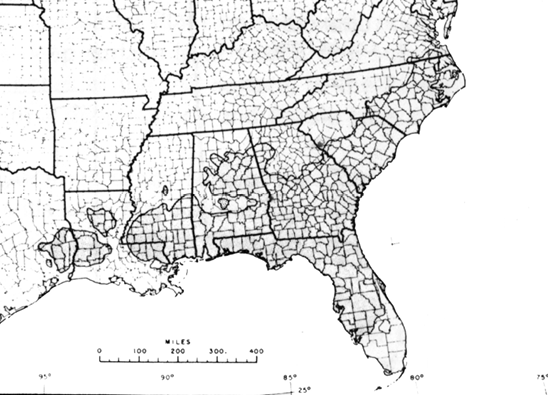

The commercial ranges of the various southern pines are shown in Figures 2 through 5. Loblolly pine is the most commonly planted, with limited acreages of shortleaf pine, slash pine, and longleaf pine planted on appropriate sites.

|

Species |

Suitable Planting Range |

Preferred Soils |

Poor Soils |

|---|---|---|---|

|

Loblolly pine |

Piedmont and Coastal Plain |

Best growth in Coastal Plain on soils with poor surface drainage, a deep surface layer with a firm subsoil (clay layer) within 20 inches of the soil surface. In the Piedmont, uneroded soils with a deep surface and friable subsoil are best. |

Deep, well-drained, sandy soils of the Coastal Plain and eroded Piedmont soils with clay subsoil exposed or near the surface. In the Coastal Plain, productivity decreases as surface drainage increases. |

|

Slash pine |

Coastal Plain |

Spodosols with depth to a clay layer greater than 20 inches from the surface. These are common soils of the “flatwoods.” They are characterized by light gray to white sands over dark sandy loam subsoils. Hardpans or fragipans that restrict root growth and downward water movement are common. |

Deep, excessively well-drained sands and very poorly drained soils. |

|

Longleaf pine |

Coastal Plain |

Generally found on well-drained to moderately well-drained, light-colored, sandy soils that are acid and low in organic matter. With proper weed control, longleaf is well adapted to more productive loamy soils |

Growth on poorly drained and excessively well-drained soils is slow. |

|

Shortleaf pine |

Northern Piedmont and Mountains |

Fine sandy loams or silt loams with indistinct profile development, friable subsoil, and good internal drainage. |

Heavy clay soils or eroded soils with clay subsoil at or near the soil surface. |

Loblolly Pine (Pinus taeda L.)

This species is found throughout Mississippi and is the most important and widely planted pine in the South. Loblolly pine produces more than half the total pine volume in the region. Since it is found on a variety of areas and sites, there has been a great deal of research into development of breeding and seed stock.

Pine tip moth can be a problem in young stands, damaging terminal shoot growth. Control with insecticides is possible; however, only practical in extreme infestations. Older trees are rarely seriously damaged by this pest. Pine bark beetles can cause excessive damage to low-vigor, overcrowded, slow-growing stands of loblolly pine. Good management practices promoting vigorous stand growth greatly reduce pine bark beetle hazards.

Genetic improvement efforts over the past several decades have yielded vastly superior seedling stocks compared to those available in the past. A wide variety of planting stocks are available to those searching for the “perfect” seedling to use in their planting efforts. For information regarding loblolly planting stock selection, see MSU Extension Publication 2617 What Are Genetically Improved Seedlings?

Slash Pine (Pinus elliottii Englem.)

Originally restricted to a limited natural range of only 7 million acres, planting greatly extended the present range of slash pine to more than 12 million acres. However, many of these plantings were planted off-site beyond the northern limits of the natural range of the species (Figure 3). These off-site plantings often suffer from ice damage and severe fusiform rust infections.

Slash pine is sometimes planted in the Lower Coastal Plain for pulp, sawlog, and pole production. Stands tend to stagnate if not thinned early to maintain adequate crown development. If thinnings are delayed until trees are 25–30 years old, little response will be gained from thinning.

Bark beetles attack slash pine, particularly during extended dry spells and after logging operations. Other insect pests, such as pine tip moth, cause only minor damage in most cases.

Slash pine is very susceptible to fusiform rust. Trees that develop galls in the main stem are prone to breakage and early mortality. Annosus root disease (annosus root rot) (Heterobasidion annosum) can invade recently thinned slash pine and loblolly pine stands. The fungus attacks the tree’s root system, ultimately killing the tree. Thinnings made during the summer lessen the chance of disease. Chemical controls were historically used during thinning operations in high-risk areas; however, the prevalence of annosus seems to have decreased across much of the South.

Longleaf Pine (Pinus palustris Mill.)

Longleaf pine once dominated the Coastal Plain forest of Mississippi and naturally occurs over much of the southern and south-central portions of Mississippi. It extends north to Claiborne County on the western border and to Kemper County on the eastern border (Figure 4).

With increased fire control over the last few decades and the inability of the species to tolerate weed competition, longleaf pine has largely been replaced in its native range by slash and loblolly pine and native hardwoods. (Periodic fires once kept competing vegetation reduced to a point where the more fire-resistant longleaf was easily established and flourished.) During the grass stage of longleaf seedlings, which may last 3–8 years, no height growth occurs. This delay of height growth allows competing vegetation to occupy sites at the expense of longleaf seedlings. Once out of the grass stage, longleaf grows rapidly, producing trees with straight, clear trunks that are highly valued for lumber, poles, and pilings.

The grass stage is shortened and successful regeneration is made possible through the use of high-quality seedlings, proper planting techniques, and adequate site preparation with herbaceous weed control during the first growing season. Longleaf is a good choice for planting on dry and intermediate sites where fusiform rust is a hazard to successful establishment and growth of slash pine.

Longleaf pine is less susceptible to bark beetles and other insect pests compared to other southern pines. Fusiform rust is not a serious problem in longleaf stands. However, in some areas, seedlings are susceptible to brown spot needle blight fungus. When brown spot infestations are severe and prolonged, seedling death occurs. Use chemical treatments and prescribed burning to control brown spot.

Shortleaf Pine (Pinus echinata Mill.)

Very few landowners plant shortleaf pine; most preferring loblolly pine due to its superior growth. However, on well-drained and drought-prone sites in the northern range of loblolly pine and where potential ice damage is severe, shortleaf pine is a viable alternative (Figure 5). In addition, recent federal restoration efforts have resulted in increasing shortleaf pine acreage planted across the species’ range. Shortleaf pine is naturally resistant to fusiform rust, but seedlings are damaged by pine tip moths. Southern pine beetles and other bark beetles can cause severe damage in shortleaf pine stands. Slow-growing stands are most readily attacked. Maintain adequate stocking and growth rate by thinning shortleaf stands to reduce serious damage from pine bark beetles.

Littleleaf disease is the most serious problem with shortleaf pine management. Trees in stands established on fine-textured soils that are periodically excessively wet and then dry begin showing stunted, yellowing needles when their age exceeds 30 years. Damage is caused by a fungus that feeds on tree roots, reducing water and nutrient uptake. Diameter growth is greatly reduced, and mortality is very high. Control is impractical with the recommended treatment being to salvage infected trees before they die or are attacked by bark beetles. After harvest, replanting strategy might consider alternate species such as loblolly pine.

Comparing Species

Table 2 provides a quick comparison of traits of the major southern pines. Consider characteristics of your planting site and geographic location when evaluating these species traits.

|

Trait |

Loblolly |

Slash |

Longleaf |

Shortleaf |

|---|---|---|---|---|

|

Fusiform rust |

2 |

3 |

1 |

1 |

|

Susceptibility to |

2 |

3 |

4 |

1 |

|

Susceptibility to |

2 |

2 |

4 |

1 |

|

Drought resistance |

3 |

4 |

2 |

3 |

|

Cold tolerance |

2 |

4 |

3 |

1 |

|

Resistance to ice damage |

2 |

4 |

3 |

1 |

|

Tolerance to poor drainage |

2 |

1 |

3 |

3 |

|

Fertility requirement |

1 |

2 |

3 |

3 |

|

Resistance to stand stagnation |

3 |

4 |

3 |

2 |

Pine species ranking: 1 = high, 4 = low

Species selection in Mississippi is normally an easy choice since loblolly pine is preferred on most sites. However, landowners in the Lower Coastal Plain have several alternatives and should compare these species to determine which is best suited to their site. A problem sometimes encountered is that of deciding between slash pine and loblolly pine. Slash was historically favored in the Coastal Plain, not only for pulp and timber production, but also as a source of resin and turpentine, along with longleaf pine. However, loblolly pine plantings have greatly increased in the region, and many landowners and foresters are unsure of the merits of loblolly over slash pine.

The following comparisons should help make the slash–loblolly pine selection in the Coastal Plain clearer. As in any planting, it is critical to match the species to the site. Soil properties and drainage are often used to decide between planting slash or loblolly pine on a particular site. General soil–site conditions and species preference are summarized in Table 3.

Other generalizations have been made to compare loblolly and slash pine in the Coastal Plain:

- Slash pine is usually preferred on wet, poorly drained flatwoods sites; loblolly is favored on moist to better-drained soils.

- Loblolly is favored on good sites where hardwood competition is a problem because slash pine is less tolerant of competing vegetation.

- Slash pine grows better than loblolly pine on poorly drained sites where phosphorus is limited (determined by a soil test) if the site is not fertilized.

- Loblolly pine is more susceptible to attack from southern pine beetles than slash pine.

|

Drainage class |

Soil horizon description |

Species preference |

|---|---|---|

|

Very poorly to somewhat poorly drained |

No spodic2 horizon; clay layer within 20 inches of soil surface |

loblolly3, slash |

|

Very poorly to somewhat poorly drained |

No spodic horizon; clay layer greater than 20 inches from soil surface |

slash, loblolly3 |

|

Very poorly to somewhat poorly drained |

Spodic horizon; clay layer present |

loblolly3, slash, longleaf4 |

|

Poorly to moderately well drained |

Spodic horizon; no clay layer present |

slash, loblolly, longleaf4 |

|

Moderately well to well drained |

No spodic horizon; clay layer within 20 inches of soil surface |

loblolly, slash, longleaf |

|

Moderately well to well drained |

No spodic horizon; clay layer greater than 20 inches deep |

slash, loblolly, longleaf |

|

Somewhat excessively to excessively drained |

No spodic horizon; clay layer may or may not be present |

longleaf |

|

Very poorly to poorly drained |

Organic surface (peat, muck) greater than 20 inches thick |

loblolly3, slash |

1 Adapted from Fisher (1981).

² Spodic horizon refers to a spodosol common in “flatwoods” areas. These soils are characterized by a surface of a light gray to white sand over a darker sandy loam subsoil. A fragipan may be present that restricts root growth and limits downward movement of water.

³ Phosphorus may be required for establishment of loblolly pine on very poorly drained soils.

4 Use longleaf only on the better drained soils in these groups.

Seed Source and Planting Zones

Landowners often buy seedlings from other states. Seedlings produced out-of-state may or may not be appropriate for some areas within Mississippi. The following guidelines will help you in selecting a source for seeds and seedlings.

Loblolly Pine

Historically, loblolly seedlings were grown from genetically unimproved seed collected from “woods run” trees. Genetic improvement has provided loblolly planting stock capable of growing and surviving across a wide range of site conditions and a level of resistance to insects/diseases unheard of a few decades ago. Consequently, many survival concerns associated with planting loblolly in the past are not problematic in today’s regeneration efforts. Some stock is more appropriate under various conditions, but as a whole, seed origin is often not a concern. For more information on appropriate loblolly selections please read, MSU Extension Publication 2617 What Are Genetically Improved Seedlings?

Slash Pine

On sites where fusiform rust is common, plant seedlings from sources with demonstrated rust resistance. If such seedlings are unavailable, rust-resistant loblolly sources or longleaf pine may be used.

Longleaf Pine

Favor local sources. Avoid seedlings from southern Florida and west of the Mississippi River. Seedlings produced from seed from central gulf states should do well.

Shortleaf Pine

It may be very difficult to find a nursery source of shortleaf seedlings. Most planting is on national forest lands. Where shortleaf pine is planted, use seedlings produced from local sources within that geographic region.

Ordering Seedlings

Once you select your species, order your seedlings from the nursery. Plan ahead to allow for adequate site preparation and to ensure availability of seedlings. Most state and private nurseries begin taking seedling orders as early as the year before planting season. Place orders early so that you have enough seedlings to meet your planting needs.

Several decisions must be made before ordering seedlings, such as how many seedlings you need and when they should be delivered. Information in the preceding sections will help you select the right species for your planting sites.

To determine the number of seedlings to order, consider these points:

- How many acres are you going to plant? Determine acreage by actual field measurement, or estimate from maps, aerial photos, or other records.

- What spacing will you use? Historically, many pine plantations were established with seedling densities in the range of 600–700 seedlings per acre. Current planting techniques typically use seedling densities somewhere between 450 and 550 trees per acre. More or fewer seedlings may be planted based on landowner objectives. A minimum of 500 pine seedlings per acre is required for participation in many federal assistance programs. In some cases, the forest industry has planted seedlings at densities of up to 1,000 seedlings per acre to maximize fiber production in short rotations for use in their pulp mills. However, most landowners will get better investment returns by planting 450–550 trees per acre and managing for late-rotation products, such as sawtimber and poles.

Seedlings are planted at different spacings to achieve the desired density. A general trend is toward wider spacing between rows for better stand access for fire control, thinning, and harvesting equipment. Compare various spacings by using Table 4.

Determine the number of seedlings required for any spacing by using this formula:

Multiply desired spacing in feet and divide that product into the number of square feet per acre. For example, how many seedlings would be required to plant 1 acre at a spacing of 9 by 10 feet?

9 feet by 10 feet = 90 square feet

43,560 square feet per acre/

90 square feet per seedling

= 484 seedlings per acre

- Make an allowance for cull seedlings. Cull seedlings are seedlings that are too small or too large to plant as well as those that die or are damaged before planting. Identifying cull seedlings is covered in detail in a later section. When ordering, allow for a 5 percent cull factor. In effect, you will be ordering 5 percent more seedlings than you calculate you need for planting. This also helps account for any shortage in the number of seedlings actually packaged. Seedlings are typically weighed for counting purposes. The final shipping count is usually an approximate number obtained using average seedling weight (the expected weight of the order is divided by the average weight of a seedling). While this method usually works well, sometimes large seedlings result in a low final seedling count.

As an example, if you order seedlings to plant 35 acres at a 7 by 10 spacing and allow for a 5 percent cull factor, you need to order 23,000 seedlings.

7 by 10 spacing = 622 seedlings per acre (see Table 4)

35 acres by 622 seedlings per acre

= 21,770 seedlings

5% cull factor: 21,770 x 1.05 = 22,859 seedlings

22,859 rounded to the next highest 1,000

= 23,000 seedlings to be ordered

|

Spacing (feet) |

Number of seedlings |

|---|---|

|

6 x 8 |

907 |

|

6 x 9 |

806 |

|

6 x 10 |

726 |

|

6 x 11 |

660 |

|

6 x 12 |

605 |

|

7 x 7 |

888 |

|

7 x 8 |

777 |

|

7 x 9 |

691 |

|

7 x 10 |

622 |

|

7 x 11 |

565 |

|

7 x 12 |

518 |

|

8 x 8 |

680 |

|

8 x 9 |

605 |

|

8 x 10 |

544 |

|

8 x 11 |

495 |

|

8 x 12 |

453 |

|

9 x 9 |

537 |

|

9 x 10 |

484 |

|

9 x 11 |

436 |

|

9 x 12 |

403 |

|

10 x 10 |

435 |

|

10 x 11 |

396 |

|

10 x 12 |

363 |

|

12 x 11 |

330 |

|

12 x 12 |

302 |

|

12 x 15 |

242 |

|

15 x 7 |

414 |

|

15 x 8 |

363 |

|

15 x 9 |

322 |

|

15 x 10 |

290 |

|

15 x 15 |

193 |

Delivery Dates

Planting season begins in December and should be completed by March, with optimum planting dates ending in mid-February. Weather conditions often force extension of the planting season, causing problems with proper seedling storage.

Early planting before cold weather can kill seedlings if they have not hardened off while still in the nursery beds. Hardening-off is a physiological process where seedlings become acclimated to colder temperatures by reaching a stage of dormancy where active growth is temporarily suspended. Some nurseries use chilling hours (temperatures between 33°F and 40°F) as an indication of dormancy. Chilling hours are monitored in the nursery, and seedlings are typically lifted after 200 or more chilling hours have accumulated. This provides seedlings that should be planted immediately or stored for no more than 2 or 3 days. When 400 chilling hours have accumulated, seedlings reach peak dormancy and can be cold-stored for up to 8–12 weeks.

If large acreages are to be planted or delays are expected, arrange for the nursery to split shipments of seedlings to allow you to store and handle a minimum number of seedlings at a time. If split shipments are not possible, make sure that you secure adequate space locally for “out-of-the-weather” storage.

Seedling Storage and Care

Pine seedlings are commonly packaged in kraft-polyethylene lined (K-P) bags or wax-coated boxes. These packages protect seedling quality during transport and storage.

Proper storage conditions must be provided before planting to maintain seedling viability. It is always best to plant seedlings as soon as possible. Do not store nondormant seedlings lifted early or late in the planting season; plant them as soon as possible. Plant longleaf pine seedlings within 1 week after lifting from the nursery. These seedlings are extremely perishable and should be planted immediately.

When your seedlings are delivered, you should be sure that they are protected from direct sun, high temperatures, and freezing temperatures. If you pick up your seedlings from the nursery or distribution point, provide cool, shaded conditions during transportation. Arrange to pick up seedlings in late afternoon and schedule long-distance hauling at night to prevent heat buildup from the sun. If an open truck or trailer is used, a tarp can shade the seedlings, but be sure to allow for ventilation under the tarp and around the seedlings to prevent heat buildup.

Cold-storage facilities offer the best conditions to store pine seedlings. Dormant seedlings packaged in bags or boxes can be kept for 8–12 weeks in cold storage at temperatures of 33–36°F and high relative humidity. Always allow excess water to drain from the seedling packages to prevent damage from decay. Discolored roots and a sour smell indicate damage from lack of water drainage. Seedlings in K-P bags and boxes do not require watering if the packages are unopened and undamaged.

After opening seedling packages, root systems should be watered to avoid root dessication.

To prevent seedlings from drying out, store them at a relative humidity of 85–95 percent. If the relative humidity inside the storage chamber falls below 80 percent, spray water on the walls and floor to increase humidity. Do not stack bags or boxes over two high, and always allow for adequate air circulation around all containers. This also prevents damage from crushing.

Most landowners do not have access to cold-storage facilities; therefore, when seedlings cannot be planted immediately, shed storage should be used to protect from wind and temperature extremes. Seedlings in bags and unopened boxes trap heat generated from respiration. This heat buildup within the packaging can damage seedlings. If storage temperatures exceed 40–50°F for several days, the vigor of seedlings in bags is reduced. Consequently, do not store seedlings for more than 4 weeks without cold storage.

Warm air temperatures will limit storage time. Allowing storage temperatures to reach 80°F can result in development of mold on seedling roots, initiating decay. Mold may be detected by the presence of fungal hyphae (spiderweb-like strands around the seedling roots) and a musty smell when the packages are opened.

If seedlings freeze, let them completely thaw before attempting to separate and plant. Immersing frozen seedlings in cool water for short periods helps speed thawing. (Do not soak for more than an hour.) Freeze-damaged root systems will appear limp and discolored, and root tips will easily slough off in handling. Discard seedlings that have suffered freeze damage. Longleaf pine seedlings are likely to be killed if frozen.

Preparing Seedlings for Planting

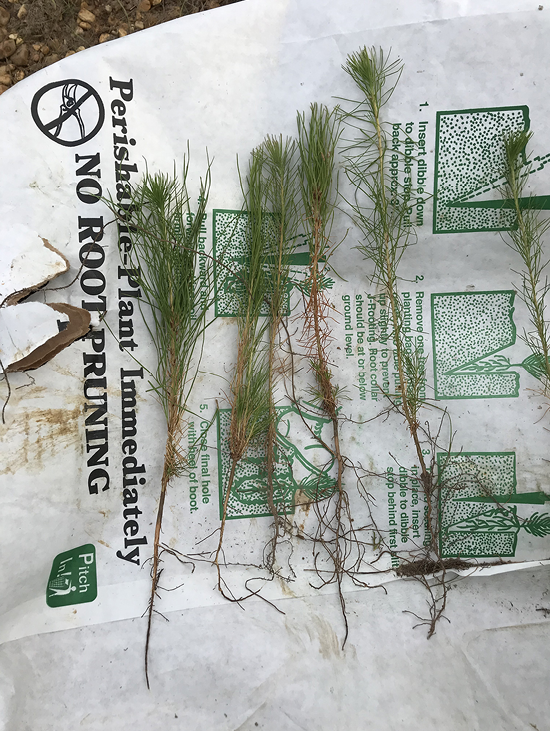

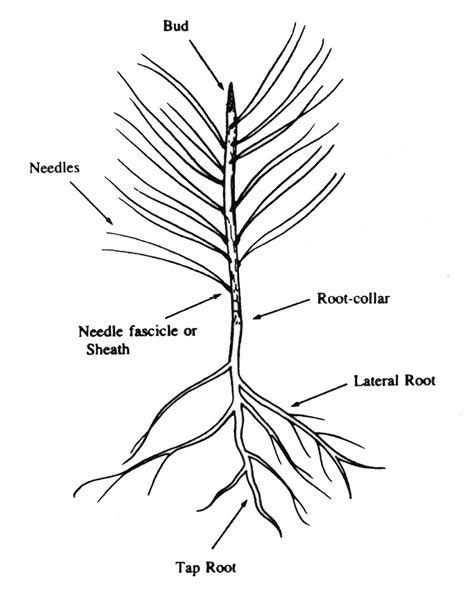

Seedlings of various sizes and quality may be in your order. Some nurseries grade seedlings to a uniform size before packaging. However, many attempt to produce a uniform seedling in the nursery bed to eliminate the added expense of hand-grading after lifting. Grading before planting removes seedlings too large or too small to be planted. It also removes seedlings with broken or crushed roots and stems, missing bark, stripped roots or needles, stem swellings indicating fusiform rust, or other damage (Figure 8).

If the nursery did not grade your seedlings before shipping, or grading efforts were insufficient, grade seedlings in a cool, high-humidity area protected from sun and wind before they are taken to the field for planting. As seedlings are removed from packaging, dip them in water, clay, or a synthetic gel root dip to reduce drying of the roots. (Check with forestry and farm chemical dealers for gel dips.) Seedlings with roots coated with kaolin clay can stand brief periods of exposure with minimal damage to roots (Figure 9).

After grading, promptly repackage seedlings in their original containers with sufficient moisture, or place them in buckets or tubs with water to keep them from drying out while being transported to the field. Do not allow seedlings to sit in water for more than 1 hour. Allowing planters to grade during planting slows work, increasing the chance of seedling mortality due to prolonged root exposure. In addition, the chance of planting cull seedlings increases due to a lack of grading consistency.

One or two people can handle grading and any necessary root pruning. Graders should know the grading standards presented in Table 5 and be aware that stem length is less important than stem root-collar diameter and root system development. Seedlings with thick, sturdy stems 6–12 inches long and well-developed root systems with five or more lateral roots have the best initial survival and growth.

|

Species |

Height (inches) |

Root collar (inches) |

Condition of stem |

Needles/fascicle |

Winter bud |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

Loblolly and slash pine |

6–12 |

1/8+ |

stiff, woody |

2s and 3s |

usually present |

|

Longleaf |

8 clipped |

1/2+ |

— |

large, 2s, 3s free of brownspot |

thickly scaled |

|

Shortleaf2 |

6–10 |

1/8+ |

stiff, woody |

2s and 3s |

usually present |

1 Adapted from May (1986).

2 Grade sand pine to shortleaf pine standards.

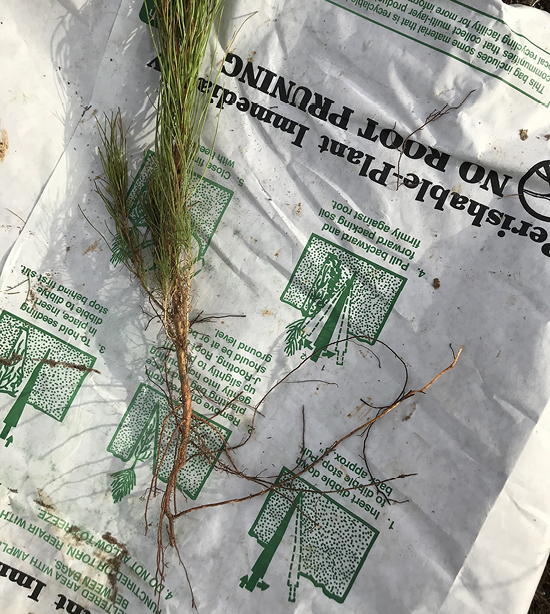

An optimum root system is 6–8 inches long with at least five to seven or more strong first order lateral roots that are at least 3 inches long. Cull all seedlings with root systems less than 5–6 inches long and those with less than three strong lateral roots. If root systems are more than 8 inches long, seedlings will be difficult to plant correctly without special care and supervision (Figure 10).

Do not allow planting crew members to prune roots during the planting operation. This results in roots being stripped off and leads to poor survival. If pruning is necessary, it should be performed by an experienced individual. Prune roots with scissors, shears, a hatchet, or a machete. Make a single, clean cut, removing as little of the root system as necessary. When root pruning is necessary, keep the pruned root system in balance with the top. Prune roots to no less than 8 inches in length for seedlings with tops of 8–12 inches.

Seedling Care in the Field

When transporting seedlings to the planting site, take only as many as can be planted in a day. If time and logistics permit, arrange to have seedlings delivered twice a day to the planting site. Load and transport packages carefully to avoid damage to seedlings.

Seedling damage occurs quickly with careless field storage and handling. Always provide a shaded storage area (Figure 11). A tarp can be erected as a canopy above seedlings to keep direct sunlight off. Be sure there is ample ventilation to prevent heat buildup in the packages. Temperatures exceeding 50°F inside seedling packaging can quickly cause seedling damage.

Do not lay a tarp directly over seedlings during the day as temperatures inside seedling packages can quickly exceed 50°F on sunny days, even when air temperatures are moderate. Cover seedlings left overnight in the field with a tarp to protect against freezing damage. Repair any tears or holes to seedling packaging with duct tape. Repackage seedlings as necessary. If seedlings are graded at the field site, be sure to do so in a cool, shaded spot protected from wind and sun.

When giving seedlings to planters, open and empty only one package at a time. Make sure planters carry seedlings in bags or buckets (Figure 12). Never allow seedlings to be hand-carried with roots exposed while planting. Have water and clay or synthetic gel dips available to keep seedling roots moist. Do not leave seedling roots in water for more than 1 hour; instead, return them to their original packaging.

Planting

The key to successful planting is the ability of newly planted seedling roots to begin quickly taking up water and nutrients. Plant seedlings in moist mineral soil where moisture is immediately available. Newly planted seedlings may be unable to take up moisture in dry soils or until drainage is achieved in flooded soils. If drainage does not occur until late March or April, container-grown seedlings can be used to extend the planting season.

Depending on the site, both hand and machine planting are efficient and reliable options. Large, open tracts are more easily planted by machine; smaller or irregularly shaped tracts, sites with minimal site preparation or cutover sites, sites with high clay content, and rocky sites are more easily planted by hand.

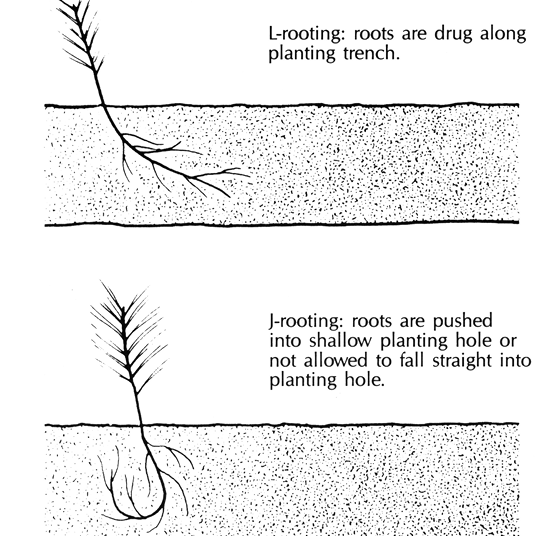

Show planters the correct depth to plant seedlings. Planting depth will vary with soil–site conditions, but always plant seedlings to a depth at least as deep as the root collar. Shallow planting results in early seedling mortality, particularly during early spring and summer droughts. On many “old field” or “old pasture” sites, soils often possess a compacted traffic pan or plow pan near the surface. In this planting situation, subsoiling can break up this restrictive layer to permit deeper planting (Figure 13). Slash, loblolly, and shortleaf pine can be planted up to 2–3 inches above the root collar, provided the planting hole is deep enough to avoid root deformation. Improper planting, resulting in J-rooting or L-rooting, slows early seedling growth and can lead to seedling mortality (Figure 14). In wet soils with a high water table, plant only to 1 inch above the root collar.

Longleaf pine requires special care in planting with great attention to planting depth. Unlike other pine species, the vast majority of planted longleaf pine seedlings are containerized stock. Plant seedlings so the terminal bud is not buried and the root collar is approximately one half inch above the surface of the ground (Figure 15).

Regardless of planting method, plant seedlings at the correct spacing and depth so that roots are oriented correctly and soil is firmly packed. This eliminates air pockets. Have a written contract detailing all planting specifications, including transport and handling of seedlings, planting dates, packing, and conditions when planting is to be suspended (site too wet or dry, freezing weather, or summer-like conditions). The contract should provide for inspections during planting to ensure that quality standards are met before payment is made. This is especially important when planting with assistance of cost-share programs.

Hand Planting

A good hand-planting crew can average up to 3,000 seedlings per man-day; inexperienced crews average far less. Most planters use a dibble bar that has a blade at least 4 inches wide and 10 inches long. Seedlings can be carried in a bucket, but a planting bag is more efficient. The planting bag is strapped around the planter’s waist. The bag will hold several hundred seedlings– and protects them from sun and wind.

The planter removes one seedling at a time after the dibble has been used to open the planting slit. Do not allow planters to carry extra seedlings in hand while planting, as they rapidly dry out. Exposure to wind and sun can kill seedlings quickly. Always provide planting bags or buckets and insist that seedlings be kept moist at all times.

Have a supervisor at the site to ensure that planting proceeds smoothly and properly. The supervisor should watch planters for poor practices, such as stripping off roots to make planting large seedlings easier, discarding seedlings to “catch up” with faster planters, shallow planting, loose packing, and carrying seedlings in hand during planting.

To ensure proper spacing, frequently check distances of planted seedlings within and between rows. Proper packing is necessary to eliminate air pockets around roots. Check by grasping several needles at the tip of the seedling between thumb and forefinger and gently trying to pull the seedling from the soil. The needles should break if the seedling is firmly packed. A shovel can be used to dig around seedlings to check for J-rooting.

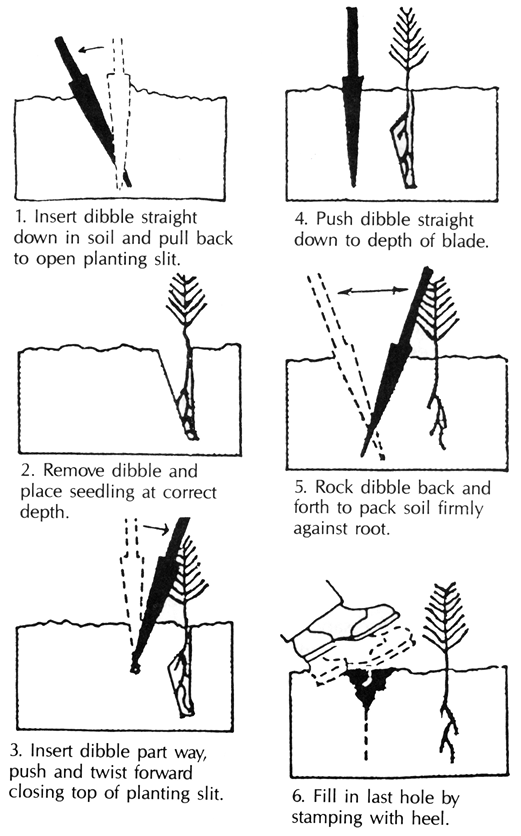

Show your planting crew the correct dibble planting technique (Figure 17):

- Insert the dibble straight down into the soil to the full depth of the blade, and pull back on the handle to open the planting slit. (Do not rock the dibble back and forth, as this causes soil in the planting slit to be compacted, hindering root growth.)

- Remove the dibble and push the seedling roots deep into the planting slit. Pull the seedling back up to the correct planting depth (1–3 inches above the roots to fall straight inside the planting slit). Do not twist or spin the seedling into the planting slit or leave the roots J-rooted.

- Place the dibble several inches in front of the seedling and push the blade halfway into the soil. Twist and push the handle forward to close the top of the slit to hold the seedling in place.

- Push down to the full depth of the blade and pull back on the handle, closing the bottom of the planting slit, and then push forward to close the top, eliminating air pockets around the roots.

- Remove the dibble, and close and firm up the opening with your heel.

Machine Planting

When machines are correctly matched to the site and operators are trained and supervised, 7,000–9,000 or more seedlings can be planted per day (Figure 18). The condition of the planting site is important in selecting the proper size of machine. Old fields and cropland can be planted with light-duty planters pulled by wheeled tractors of 30–100 hp. Rough sites require the use of heavy-duty planters pulled by large farm tractors or crawler tractors of 50–350 hp.

Seedlings are planted with machines using two systems: a manual system, where the seedling is placed into the trench by hand, or an automated system, where seedlings are placed in “fingers” that then place the seedlings into the planting trench.

Frequently check planting performance to ensure proper planting, particularly when soil type, texture, moisture, or amount of harvest debris changes on the site. Maintain proper adjustment by carefully checking planting performance under actual site conditions. Adjust packing wheels to completely close the planting trench from top to bottom. Be sure seedlings are planted straight and at the proper depth. Follow the planter and use a shovel to open the planting trench to judge root placement.

L-rooting is a common problem with machine planting. Adjust the planter to open the trench to maximum depth, and make sure seedlings are placed at the proper depth and released quickly so roots are not dragged along the trench.

Planting Conditions

Carefully check the site and environmental conditions at planting time. Planting on bright, sunny, windy days in dry soil can result in increased seedling mortality. Dry soil is difficult to pack around seedling roots. When soils are too wet, especially clay soils, machine planting can result in soil compaction around seedlings, as well as other site damage.

Optimal planting conditions are when temperatures are between 35°F and 60°F with relative humidity greater than 40 percent and wind speeds less than 10 mph. When air temperatures are in the 70s and low 80s with low humidity (less than 40 percent) and wind speeds of 10 mph or greater, plant cautiously, as seedlings can quickly dry out after planting.

If the situation allows, delay planting until conditions improve, or plant in afternoon hours when seedlings will face less environmental stress. If planting must continue under these conditions, have planters carry fewer seedlings and take extra precautions to prevent them from drying out. Do not plant in freezing weather or summer-like conditions when temperatures are below 32°F or above 85°F.

Container-Grown Seedlings

Seedlings produced in containers have become increasingly available in the South. In fact, nearly all longleaf pine seedlings planted will be container-grown. Container-grown stock offers the advantage of extending planting season length compared to that of bareroot stock. Using container-grown seedlings, early-season planting in the South can begin as early as October, allowing seedlings to become established before freezing weather occurs. Planting can extend into late spring and even summer on sites that may be too wet to plant during the fall or winter with bareroot seedlings. The protected root systems of container-grown seedlings reduce the damage associated with lifting, storing, and planting bareroot seedlings.

Seedlings are best stored in their containers where they are protected from root damage and drying out. Protect them from freezing, as root plugs can easily freeze. The limited soil volume of the container makes seedlings susceptible to drying out in sunny and windy conditions. Store in partial shade, and water frequently to maintain adequate moisture throughout storage and planting.

Container-grown seedlings may be machine- or hand-planted, but in both methods, should be deep enough to cover the root plug completely with soil. If the top of the root plug is not covered, it will rapidly dry out and the seedling will die. Take special care when planting container-grown longleaf pine seedlings. If planted too deeply, the bud will be covered; if planted too shallowly, the root plug will be exposed, which rapidly dries out the rooting media. Typically, longleaf pine seedlings should be planted with approximately one half of an inch of the plug above the ground surface.

Evaluating Planted Stands

Survival and stocking are two important factors in evaluating the success of your planting efforts. Survival is the number of planted seedlings alive at the time of your observations. It is best estimated by establishing permanently marked plots soon after planting. Seedlings are then counted at the end of the first growing season and compared to the initial number of seedlings in plots. Ten to 20 well-distributed plots are usually sufficient for survival estimates.

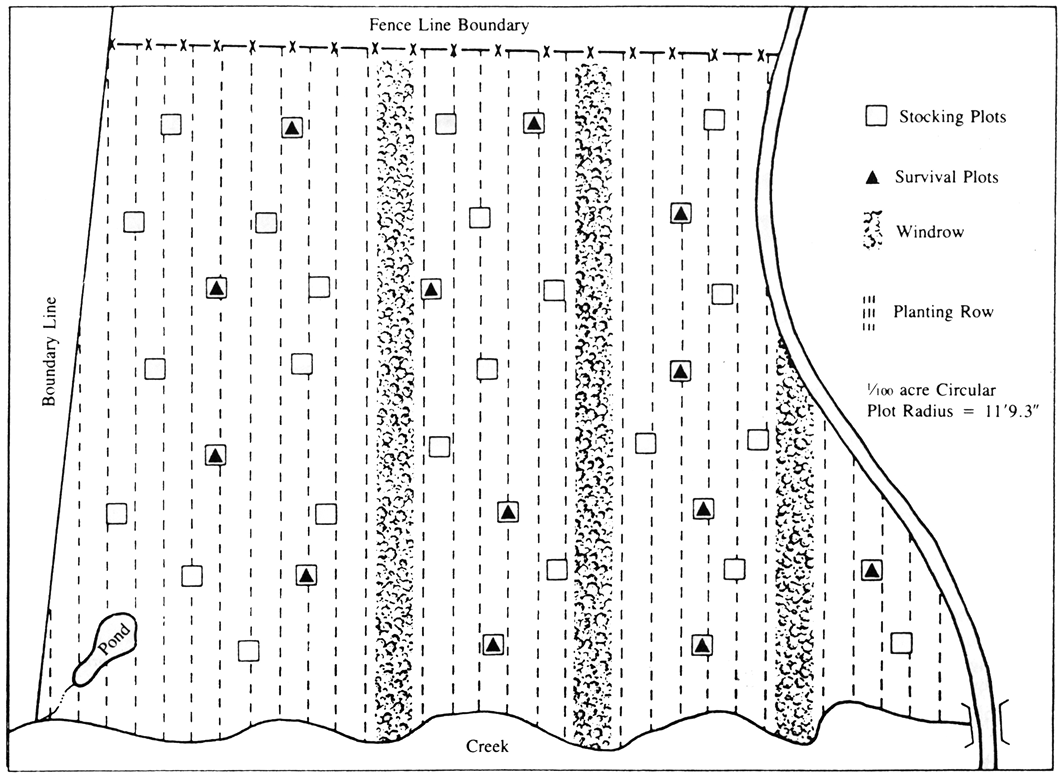

Stocking represents the number and distribution of living seedlings across the plantation. This information is used to determine whether replanting a portion or the entire stand is necessary. A systematic sampling system is the best way to sample stocking. The number of live trees is counted in fixed-area plots, usually circular plots. These plots are uniformly spaced across the plantation (Figure 19). Plots of 1/50 acre to 1/100 acre in size are convenient.

You need 40–60 plots to get accurate estimates of first-year stocking, regardless of plantation size. Orient sample plots on lines that cross planting rows throughout the entire plantation.

Replanting

If the survey reveals that at least 300 seedlings per acre are evenly distributed over the plantation at the end of the first growing season, replanting or interplanting will not be necessary. If there are large areas with poor stocking, these areas can be replanted, but additional site preparation may be required.

Avoid interplanting skips within rows. Newly planted seedlings do not compete favorably with established older seedlings. Interplants seldom add to volume production at harvest, and the added investment cost for seedlings and planting will not be recovered.

If you attempt interplanting, plant no closer than 20 feet to an established seedling. Interplanting may be required in stands established under federal incentive programs to meet minimum stocking requirements. If so, spot herbicide treatments for weed control around interplants may aid their survival and growth.

References

Balmer, W.E., and H.L. Williston. 1974. Guide for Planting the Southern Pines. USDA Forestry Service Southeastern Area State and Private Forestry Publication.

Ezell, A.W. 1987. Hand vs. Machine Planting. Forest Farmer, 47(1).

Fisher, R.F. 1981. “Soils Interpretations for Silviculture on the Southeastern Coastal Plain,” Proceedings of the First Biennial Southern Silvicultural Research Conference. USDA For. Ser. GTR SO-34.

May, J.T. 1986. “Seedling Quality, Grading, Culling, and Counting,” Southern Pine Nursery Handbook. USDA Forestry Service, Southern Region Cooperative Forestry Publ.

Self, B. 2021. What Are Genetically Improved Seedlings? MSU Extension Publication 2617. 4p.

Schultz, R.P. 1997. Loblolly pine: The ecology and culture of loblolly pine (Pinus taeda L.). Agriculture Handbook 713. Washington, D.C.: USDA Forestry Service. 493 p.

The information given here is for educational purposes only. References to commercial products, trade names, or suppliers are made with the understanding that no endorsement is implied and that no discrimination against other products or suppliers is intended.

Publication 1776 (POD-10-22)

Revised by Brady Self, PhD, Associate Extension Professor, Forestry, from an earlier edition by Andrew W. Ezell, PhD, Professor and Emeritus, Forestry. Front page photographs courtesy of Andrew Ezell, PhD, and Randy Rousseau, PhD; USDA Forest Service; and Bugwood.org.

The Mississippi State University Extension Service is working to ensure all web content is accessible to all users. If you need assistance accessing any of our content, please email the webteam or call 662-325-2262.